Unhealed wounds: deathtoll of Yugoslav wars still unknown

People living on the Balkan Peninsula. can still vividly remember the conflicts of the past decades. Many families suffered heavy losses because of the ethnic wars of the 90s, and the region is still divided.

Independence born as a result of bloody wars

Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Bosnians, Kosovars and Montenegrins suffered serious losses due to the ethnic wars of the 90s. The independence aspirations of members within the former Republic of Yugoslavia ended in war and bloodshed in the Balkans with fighting raging on for 10 years in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo. NATO also deployed airstrikes against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which in 1999 comprised Serbia and Montenegro.

The goal of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was for the Yugoslav government troops to withdraw from Kosovo to avert a humanitarian disaster in the region, where – according to allegations – the Serbs had been carrying out ethnic cleansing against the Albanian population. The attack, which lasted 78 days, went ahead despite not receiving an approval from the UN Security Council. The airstrikes ended after Belgrade withdrew its troops from Kosovo. Serbian forces have not returned there since, even though Serbia does not recognize Pristina’s independence.

NATO airstrikes also claimed civilian casualties

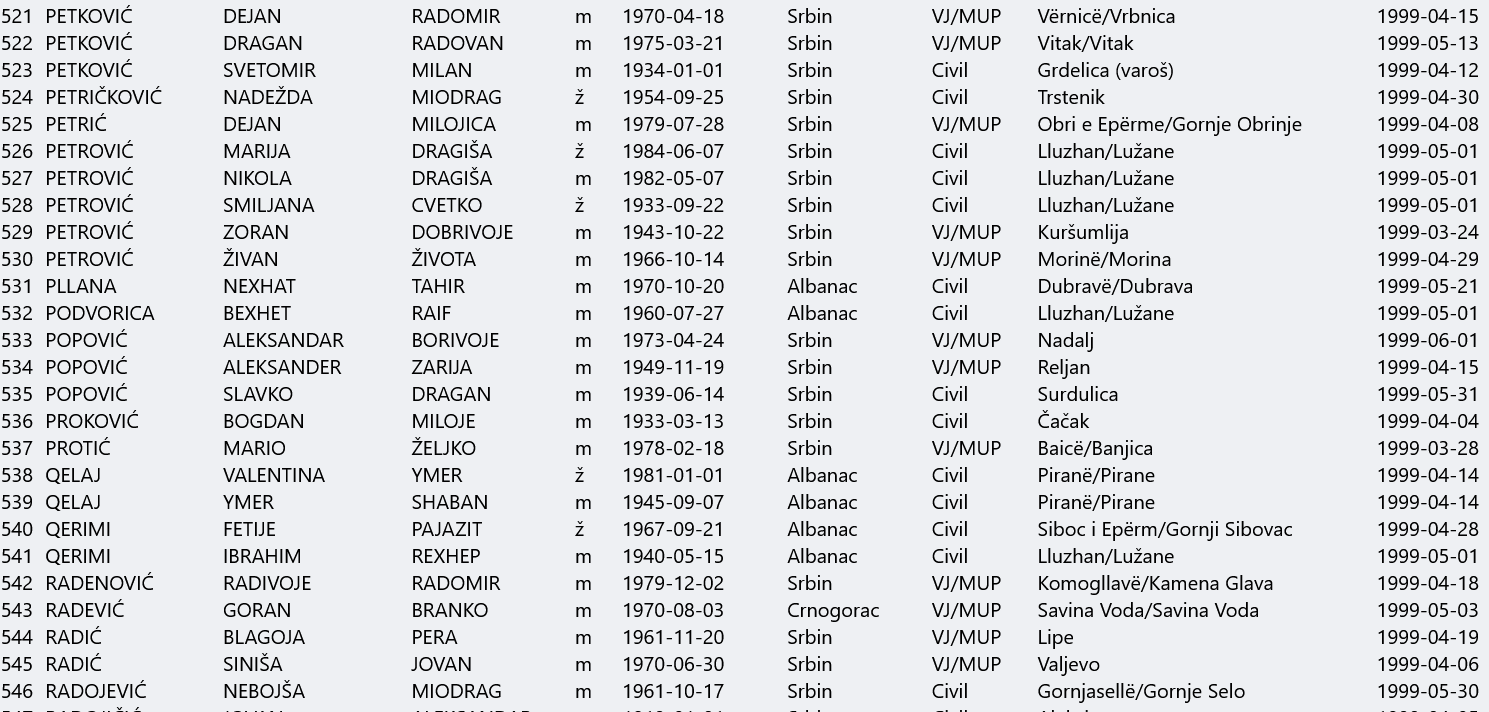

On the first of May 1999, when a bus, Nis Express, was crossing the bridge 20 kilometers from Pristina, an incoming bomb destroyed the bridge and split the bus in two. Nikola Petrovic, his sister and grandmother, Smiljana, were travelling on the bus. 39 civilians died, their bodies lying strewn across the area.

At the time, NATO leaders expressed regret for the incident, but the organisation pointed out that the bridge was a legitimate military target. Marija Petrovic was 15 years old when her brother Nikola died. He would have finished secondary school that year. The members of the Nikola family were returning home from Prokuplje, Serbia, to celebrate his birthday.

The children’s mother, Zorica, was home alone when she heard on the radio that a rocket had hit the bridge on which there was a bus. The woman tearfully told the press that she knew her relatives were on that bus. When she heard the news, she fell to the ground and started sobbing, she recalled.

„Many years have passed, but it’s just as difficult for us, we have lost hope,” says Zorica. Official notification of the death of her family members came three days later. The news was brought by a neighbour, because the phone lines weren’t working at the time, either.

“I knew, I just knew right away that they had died. I knew that they were on that bus,” says the mother. The situation was compounded by the fact that the head of the family, Dragisa, was not at home either, because he was doing military service near the Albanian border.

A few days after the incident the father was able to travel to Pristina to identify the bodies of his children.

„I recognised Nikola from his cross, and Marija had a special necklace, but I also identified my mother,” Dragisa recalled.

Radio Television of Serbia has produced a number of programmes on the victims of the NATO bombing. The documentaries made by the public broadcaster featured contemporary footage and victims’ testimonies.

No exact data on civilian death toll

Twenty-three years after the events, there are still no accurate figures on how many people died in NATO airstrikes in Yugoslavia. Veljko Odalovic, director of the Serbian government’s Office for Missing Persons, explained this by saying that it was impossible to cooperate with the Kosovo leadership. The Pristina government refuses to provide data, he said, adding that victims included Serbs, Albanians and citizens of other nationalities.

Photo: Facebook

The most reliable data was released by the NGO Humanitarian Law Center, which compiled a list, complete with names and birth years of victims, who died in the 1999 air campaign. In their tally, 452 civilians lost their lives. This list also includes above-mentioned Nikola Petrovic and his family.

Serbia, however, has never released official figures on how many Serb soldiers and police officers died. Authorities tend to relay aggregate fatality figures to the public.

NATO and US remain unpopular with Serbs

Serb society still vividly remembers the horrors of the bombings and for this reason becoming a NATO member is widely opposed, as shown by survey results. The United States is one of the most rejected countries, as a poll by Ipsos found, revealing that merely 8 per cent of the citizens hold a positive view of the overseas superpower.

The disapproval rating of the US is high because of the NATO airstrikes and the Yugoslav wars. The number of those who support Serbia’s joining of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation is at historic lows, with only 5.4 per cent supporting the NATO membership.

Tensions could resurface in the Balkans

Slovenia has celebrated the 31st anniversary of its independence recently. The wealthiest former republic of Yugoslavia gained its sovereignty at the cost of the so-called Ten-Day-War. The new, left-wing Ljubljana government has made decisions in recent days that could harm the country’s peaceful, rich jewel-box image. The government decided to dismantle the fence built on its border with Croatia, clearly inviting migrants in to the country.

Slovenia has been trying to educate and sensitise its citizens to become more inclusive for years now. For instance, in a film produced in 2007 to promote the country’s image, every Sloven person’s role is played by actors of colour.

The film also highlights a typical Slovene characteristic of striving to resemble Austrians and Italians, their western neighbours. Apparently, they have made concrete steps towards welcoming migrants, following in the footsteps of former Chancellor Angela Merkel.